<center>

# How math makes matches meaningful

<big>

**In this blog, we show you how finding the right algorithm can make the difference when it comes to creating meaningful, professional connections virtually.**

</big>

*Written by Ben Dichter and Mirjam Guesgen. Originally published 2022-07-18 on the [Monadical blog](https://monadical.com/blog.html).*

</center>

The science of matchmaking used to be, well, let’s just say less than scientific.

In the [1920’s](https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/mechanical-matchmaking-the-science-of-love-in-the-1920s-103877403/?no-ist), couples endured a series of experiments to test their compatibility. One involved a partner smelling the other using a large dome with a hose coming out of it. If they could withstand the smell, a match was made.

>Sniffing out a potential match. April 1924 issue of Science and Invention magazine.

Romantic matchmaking has come a long way from smelling domes to now having an algorithm show you potential dates based on your preferences. What used to be a matter of luck or careful planning by a nosy relative can now be a calculated and optimized endeavour.

But it’s not just in romantic matching where technical tools can trump sniffing out the right match. There are numerous scenarios in the professional world where finding the right match organically can be difficult but doing so can be extremely valuable.

Anyone who’s been to a networking event will tell you it’s a lot like dating. You dress up, pull yourself together and scour the room (sometimes awkwardly) trying to find someone you click with. Wouldn’t it be easier if everyone had a great big sign over their head showing you how much you might have in common? Or that this person is working in the same field you are?

After graduating as a neuroscientist, I wanted to find a way to connect neuroscience theorists with experimentalists. I’d been to “speed dating” type networking events at conferences before but now I wanted a way to simulate a similar experience virtually, where you’d evaluate your colleagues’ interests, list who I’d like to speak more in depth with and then follow up with a one-on-one.

I found that virtual events aren’t natural breeding grounds for the same kinds of discussions that might happen serendipitously over the lunch table or through a well-planned sit-down coffee chat.

That’s when we set out to develop Zohuddle. Zohuddle is an app that matches two people in one-on-one “huddles”, and then hosts those huddles through in-app video chat.

But the secret sauce to Zohuddle lies in having the right algorithm behind it to form the kind of meaningful matches we want. With meaningful matches, it’s possible to unlock the real potential of virtual conferences and meetings: global connections between hundreds of people, lower costs and lower carbon emissions.

Not all algorithms are created equal. So here, we’ll discuss five approaches for matching and their trade-offs.

## The problem

Picture yourself as a conference organizer setting up a networking event. The networking event takes place over a day, with, let’s say, six time slots for one-on-one meetings.

The goal is to match people who are interested in talking to one another and provide the opportunity for meaningful connection. So, what approach do you use?

## 1. Random matching

The easiest approach would be to assign matches completely randomly.

It’s simple, sure, and doesn’t require any information about the attendees or a complicated algorithm. But that’s precisely where it falls short. Random matching doesn’t factor in anything in terms of people’s areas of research or preferences for who they want to meet.

You might get lucky and pair together attendees who could collaborate but it’s just as likely you’ll end up with matches that don’t go anywhere and waste time.

This might be ok if you’re running a very domain-specific event, or trying to match people socially or for fun. It’s less useful if participants are seeking something specific from the matches. If your goal is a meaningful connection, then this approach might fall short by a long way.

## 2. Gale-Shapley matching

Medical residency matching is faced with a similar problem, where residents need to match with residency programs, and matching randomly wouldn’t be a good solution.

Several [residency matching programs](https://www.nrmp.org/intro-to-the-match/how-matching-algorithm-works/) use the Nobel Prize-winning approach, the [Gale-Shapley algorithm](https://econ.ucsb.edu/~tedb/Courses/Ec100C/galeshapley.pdf). Here, applicants rank schools and residency programs by preference, and residency programs also make a ranked list of their preferred applicants. The algorithm goes through the preferences of each applicant and tries to match them to their preferred programs. The applicant is admitted to the program based on where they fall on the program’s list of preferred applicants.

It works like this: Each program creates a ranked list of its preferred applicants. The highest ranking applicant to that program will get accepted; then the next highest ranking and so on down the list of applicant popularity. The matching ends when either every applicant is paired or they’ve been rejected by every program they have applied to.

It’s an elegant design that finds an optimal solution, taking both parties’ preferences into account.

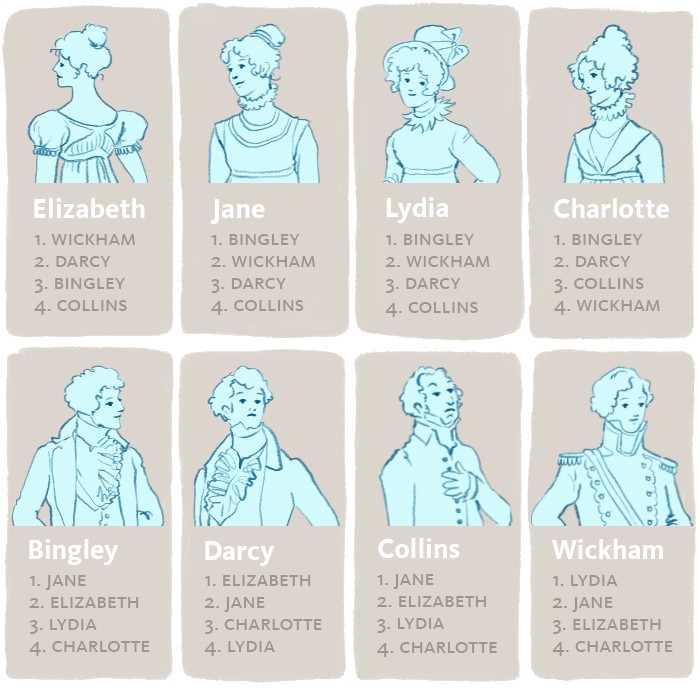

>Gale-Shapley matching was originally proposed as a way to ensure stable marriages. Here, Pride and Prejudice ladies and gentlemen pick their preferred matches. [Credit](https://medium.com/@UofCalifornia/how-a-matchmaking-algorithm-saved-lives-2a65ac448698): University of California.

>The ranked ordered lists of the ladies are then compared against those of the men and matches are made. In the marriage example, the ladies are akin to applicants in the residency example, and the gentlemen are the programs. [Credit](https://medium.com/@UofCalifornia/how-a-matchmaking-algorithm-saved-lives-2a65ac448698): University of California.

<br>But, when it comes to our networking scenario, Gale-Shapley matching is not ideal for a couple of reasons.

For one, the algorithm is asymmetrical, and the preference of one side is given more weight than the other. The outcomes of the algorithm depend on who’s doing the proposing. In the case of residencies, the matching is said to be “applicant-proposing” and therefore favours the applicant. In a networking scenario you’d have to choose which of the two groups of conference attendees you want to favour.

Problem number two is that Gale-Shapley matching only really works for pairing two distinct parties. In a conference setting, it’s not always possible to form two distinct lists of people that want to be paired with one another.

Finally, this kind of matching only gives you one match. Your networking event is going to be pretty pitiful if each person only has the opportunity to meet one other person!

## 3. Proximity matching

In proximity matching, the goal is to match participants that are most similar to each other. An example is the 2020 [Neuromatch](https://www.simonsfoundation.org/2020/04/03/designing-a-virtual-neuroscience-conference/) conference, which used a version of this called semantic matching. In semantic matching, the algorithm analyzes submitted bios from attendees and creates matches between participants whose bios are most similar.

To figure out this similarity, the Neuromatch conference algorithm first identifies the most meaningful words. It then creates a vector that represents the topics present in that bio.

The semantic matching algorithm then pairs people based on which vectors are closest to one another in the topic space. Conference participants could also select anyone they don’t want to match with.

You can then use these proximity scores in a mixed integer program. This works out the optimal schedule that minimizes the distances between matched bios, and ensures no one is double-booked and the same two people do not meet twice.

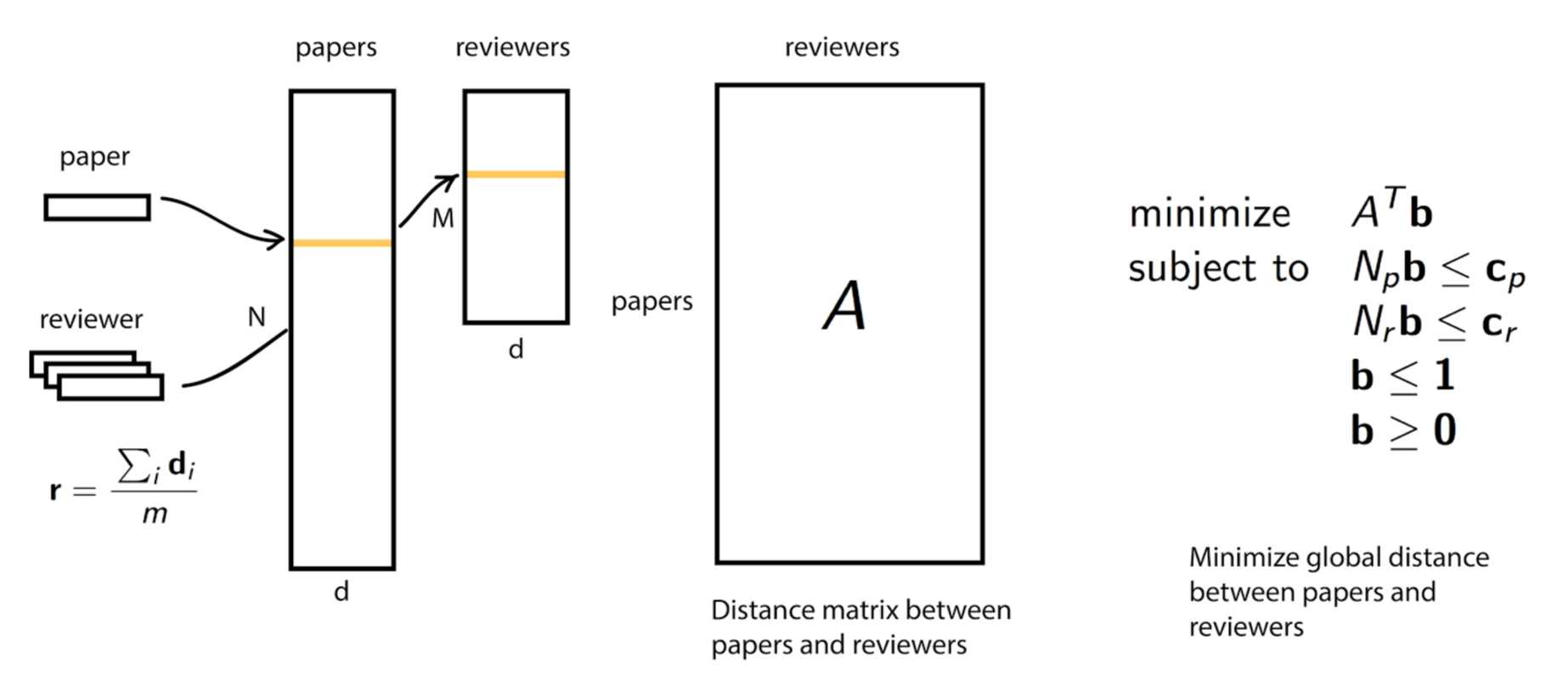

>A schematic of how the proximity matching algorithm behind Neuromatch works. It was originally based on the problem of assigning papers to reviewers given particular constraints. GitHub code [here](https://github.com/titipata/paper-reviewer-matcher).

On the plus side, semantic matching makes light work out of matching thousands of bios. Great when you’re short on time or don’t want to trawl through and read bio after bio to make your preference list. It’s done for you.

But semantic matching also has a few potential downsides. Maybe the most obvious is that it only pairs people with similar bios, which is no good if participants want to find someone with a dissimilar research area, skillset or interest. Some of the most memorable conversations can come from meeting someone with a totally different perspective!

It’s also a very automated approach, which takes a bit of the personal aspect out of matching. It just feels nicer than knowing that a person, rather than a computer alone, picked you out of a crowd.

## 4. Rank matching

In rank matching, participants make a ranked list of their favourite people to match with (similar to Gale-Shapley matching). These top choices get ranks 1, 2, 3, etc. and anyone not chosen is given the maximum rank plus one, ensuring they’re the least preferred.

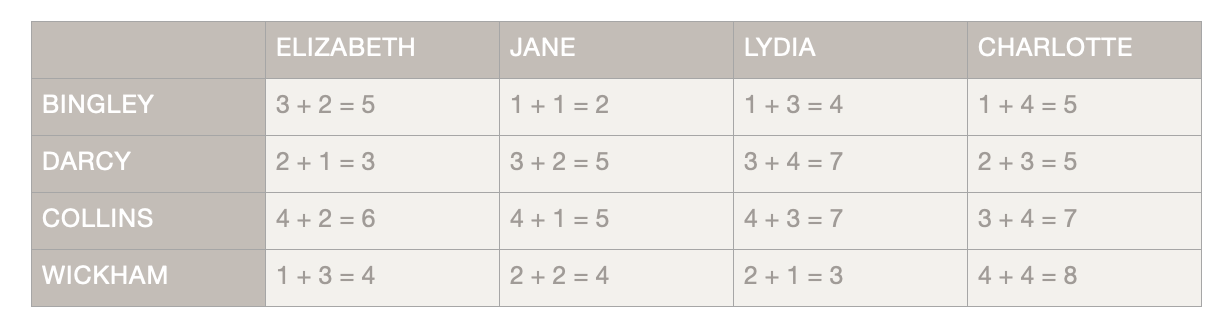

The algorithm then adds the ranks for each potential pair of people. From here, rank matching uses the same mixed-integer approach as proximity matching. In this case, instead of optimizing to find the least distance between vectors of topics, the algorithm is finding the lowest summed rank (that is, as close to each person’s first choice as possible). Again, it also makes sure there are no repeat matches or double bookings.

It takes people’s preferences into account and finds the best matches, similar to Gale-Shapley matching, but doesn’t rely on having two distinct groups of people or a proposer and an acceptor.

>Table showing the summed ranks for the Pride and Prejudice example. Rank matching doesn't rely on having a proposer and can be done for more than two groups of people.

Rank matching might be feasible if you’ve got a lot of time, or not many people to sort through. The downside is it still relies on each participant knowing a little about all the other conference goers, so that they can select their preferred matches. In a conference with potentially hundreds of participants, reading through everyone’s conference bio would just take an unfathomable amount of time.

## 5. The hybrid approach

Our solution is to combine approaches three and four. First, we use semantic matching to propose our best guess of who a participant might be interested in meeting based on interest proximity. Then participants can tweak those preferences to their liking, and create the rankings that will be used for the mixed-integer programming.

This approach provides the best of both worlds – attendees don’t need to read every bio to get reasonable matches, and they still have the option to personalize their choice to match with anyone, even if they have very different topics in their bio.

## The optimized endeavour

Finding the right match in 2022 – professional or personal – no longer relies on chance, who happens to live in your local community or who you happen to run into reaching across the salad bowl.

Matching can be an optimized and efficient endeavor. The right algorithm has the potential to find and connect communities, better, faster, and with potentially stronger bonds later on!

It’s just about finding the right algorithm to *match* the situation!