<center>

# How to Fit All Human Knowledge in a Box

<big>

**How we used the power of Cython to help streamline the way that knowledge can be packaged and shared all over the world -- even without the internet.**

</big>

*Written by Tess McCrea and Juan Diego Caballero.

Originally published 2020-08-11 on the [Monadical blog](https://monadical.com/blog.html).*

</center>

## Knowledge for All!

If you asked for a list of the three things we love most excessively at Monadical, I might say open source projects, free exchange of information, and all forms of learning. So we were all super excited when Kiwix founder Emmanuel Engelhart contacted us a few months ago after coming across our co-founder Nick’s open source side-project [archivebox.io](https://archivebox.io/) (a tool to allow people to create their own self-hosted archives or their favourite pieces of the internet). If you haven’t heard of Kiwix, they’re awesome -- they’ve created a whole suite of open source software components to compress the world’s greatest repositories of human knowledge, starting with [Wikipedia](https://www.wikipedia.org/) and now including stuff like [Project Gutenberg](https://www.gutenberg.org/), [Stack Exchange](https://stackexchange.com/), [YouTube](https://www.youtube.com/) and [Ted Talks](https://www.ted.com/talks), as well as an offline browser to access all this info.

“Cool,” you may be thinking, Hypothetical Reader, “I’d love to have Stack Overflow at my fingertips while I’m trying to debug on an 8-hour WiFi-less flight”. Or perhaps, “Great! Next time the power goes out I’ll still be able to learn about how to [maximize my misery](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LO1mTELoj6o) most efficiently!”.

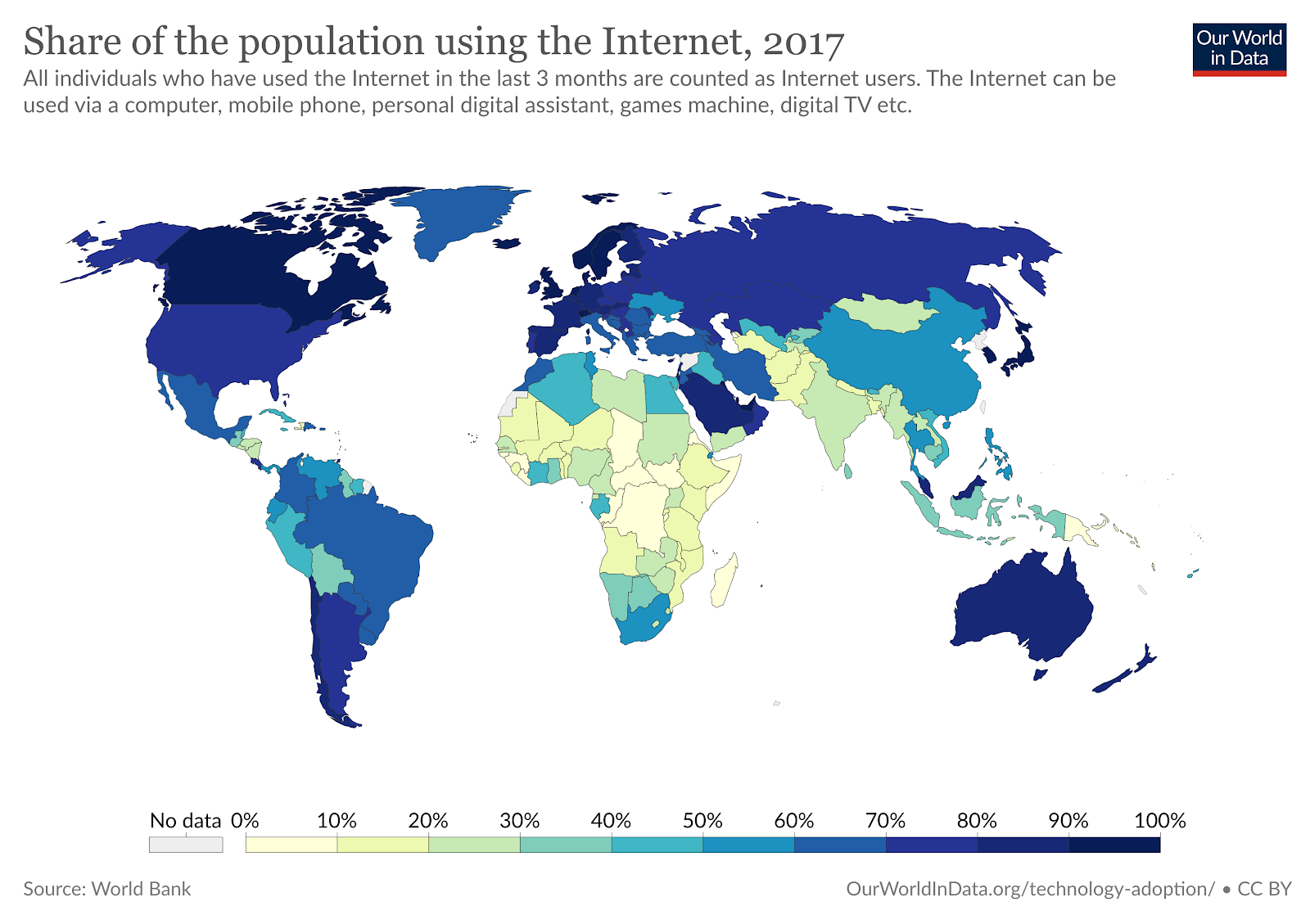

And, indeed, you will! However, in addition to these noble use cases, Kiwix lets people who don’t have internet access, or who have limited internet access, utilise the massive wealth of human knowledge many of us take for granted. If you’re like me, you probably barely even register the fact that you have virtually instantaneous, constant access to an unimaginable trove of information (and, of course, [seductive radishes](https://www.sadanduseless.com/radish-hotness/?fbclid=IwAR1_psKlYDxE2vy4Uk55ku83hzBKgIIP0O6-vs0Nn53HVfjQyEvpuq2t7uk)) anymore. But did you know that according to a [2017 study](https://www.itu.int/dms_pub/itu-s/opb/pol/S-POL-BROADBAND.18-2017-PDF-E.pdf) by the UN Broadband Commission for Sustainable Development, over half the world’s population (close to **4 billion** people!) doesn’t have access to the internet? The main reasons are lack of infrastructure and lack of affordability -- an issue of growing concern in a world increasingly reliant on digital information exchange.

And that’s to say nothing of countries where the information access is heavily controlled or tracked -- Wikipedia itself has been [intermittently censored or banned outright](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Censorship_of_Wikipedia) in countries as varied as the U.K., Russia, Venezuela, and Turkey. In China, Wikipedia is blocked in its entirety. In Cuba, internet infrastructure is increasingly available, but private internet access remains prohibitively expensive (in part due to the U.S.’s historical trade embargo), and all internet usage is heavily [monitored by the government](https://freedomhouse.org/country/cuba/freedom-net/2019). According to freedomhouse.org, which produces yearly Freedom on the Net reports tracking internet access, freedom of expression, and privacy issues in 65 representative countries around the world, as of 2018, [internet freedom is on the decline](https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-net/2018/rise-digital-authoritarianism#:~:text=Freedom%20on%20the%20Net%20is,internet%20freedom%20conditions%20each%20year.) overall -- including in the U.S.

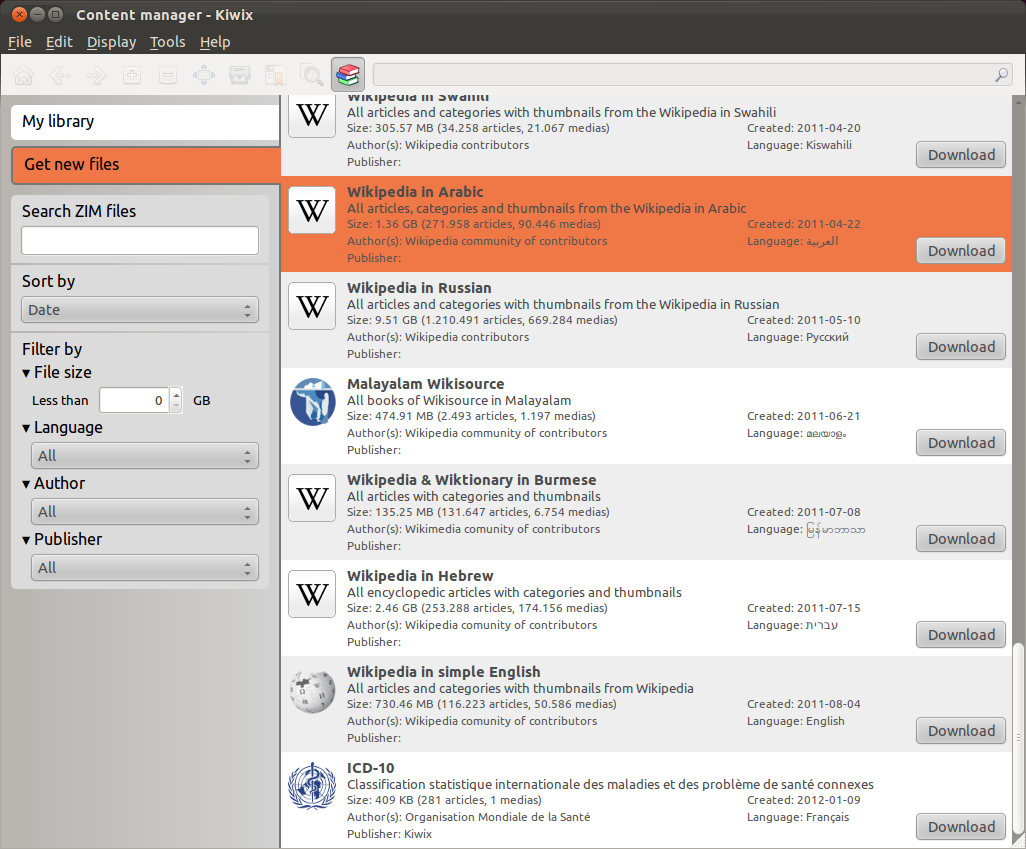

With Kiwix, massive knowledge bases are bundled and organized for offline use. They can then be downloaded directly by users with unreliable or low-bandwidth internet (the method used by the [Afripedia Project](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Afripedia_Project)), or accessed via USB or external hard drive.

<center> Kiwix offline browser with files available for download.

</center>

## The Problem:

I hear you, dear Hypothetical Reader, saying to yourself “Great, I’m definitely convinced that Kiwix is awesome! But what does it have to do with Monadical??”

Oh, Hypothetical. You always know just the right question to ask.

As you can imagine, bundling massive amounts of internet-based content into a downloadable and browseable file comes with some challenges. Basically, Kiwix created a library called libzim, and content (images, videos, text, links, etc.) is scraped from internet-based sources and put into the library. The library bundles and organizes it into what’s called a [ZIM file](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ZIM_(file_format)), which users can acquire (by download, or on a USB stick, for example) and browse using the [Kiwix ZIM reader](https://www.kiwix.org/en/downloads/kiwix-reader/).

Sounds simple, right? Not so fast!

The library is written in C++. This makes sense, because C++ is a relatively low-level language, meaning that it’s closer to machine language (think ones and zeroes), compared to a higher-level language, which is more abstracted from machine language, and closer in syntax and structure to human language. Lower-level languages are faster to execute than higher-level languages, and the programmer has direct control over how memory is handled, which makes it ideal for a library like libzim. So far, so good!

However, the content scraper is written in Python. Uh-oh. This meant that the library couldn’t communicate directly with the scraper.

“Uh...then why was the scraper written in Python?” I hear you asking. So inquisitive!

A higher-level language like Python, which is closer to human language, is more “natural” and easier to use for a lot of programmers. In C++, tons of information is needed from the user in order to make it work, while Python comes with a lot of built-in data structures like vectors, dictionaries and iterators that make it easier to use right out of the box.

Nowadays, self-taught programmers more often opt for the softer learning curve Python offers, and universities have been coming to similar conclusions. C programmers (who are proficient in C languages like C, C++, and C#) are increasingly uncommon, and having the scraper in Python made it more accessible for contributors, and easier to adapt to different data sources. Usually, only sections of code that need to be optimized are written in low-level languages like C/C++, as modern computers are plenty fast anyway, and it's much more time-consuming to write low-level code. Basically, developer time is usually the limiting factor, as opposed to processor cycles.

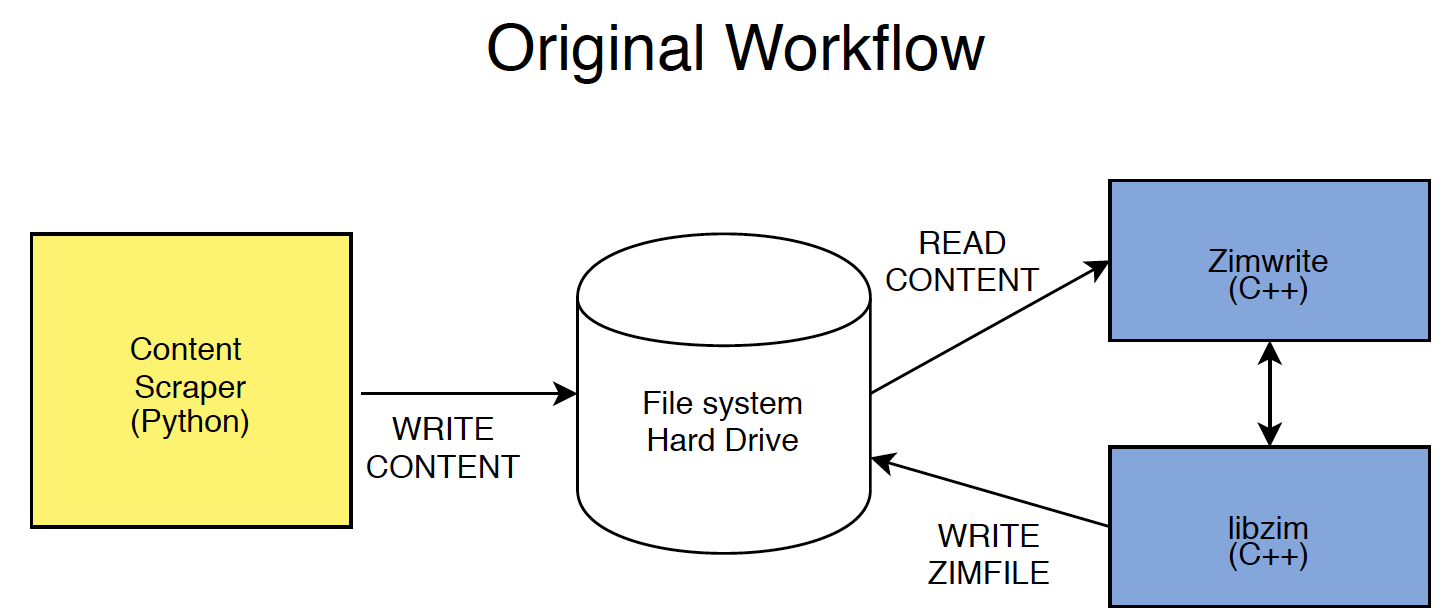

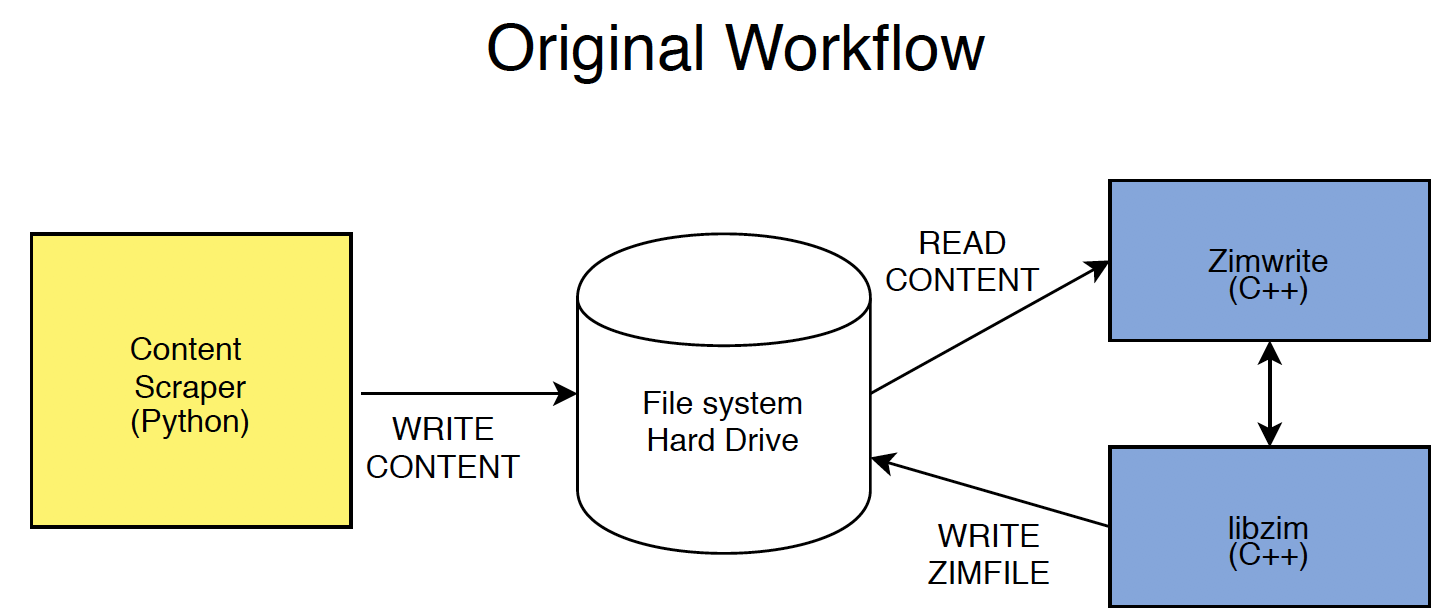

Kiwix’s workaround for the communication problems between the scraper and the library was to use a disk (the file system hard drive) as an intermediary. Content scraped by the scraper was copied onto a disk, which was then bundled into the library by another tool, so that the library could create the ZIM file:

As you can imagine, this workflow was non-ideal; it was slow and took up a lot of disk space. In addition, using the library to write more complex data sources was complicated and difficult. Generally speaking, using the hard disk as RAM is something to be avoided, because of the computer’s [memory hierarchies](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Memory_hierarchy).

Fixing it would require a mechanism that could communicate in both worlds. That's where Monadical came in.

## Our Solution:

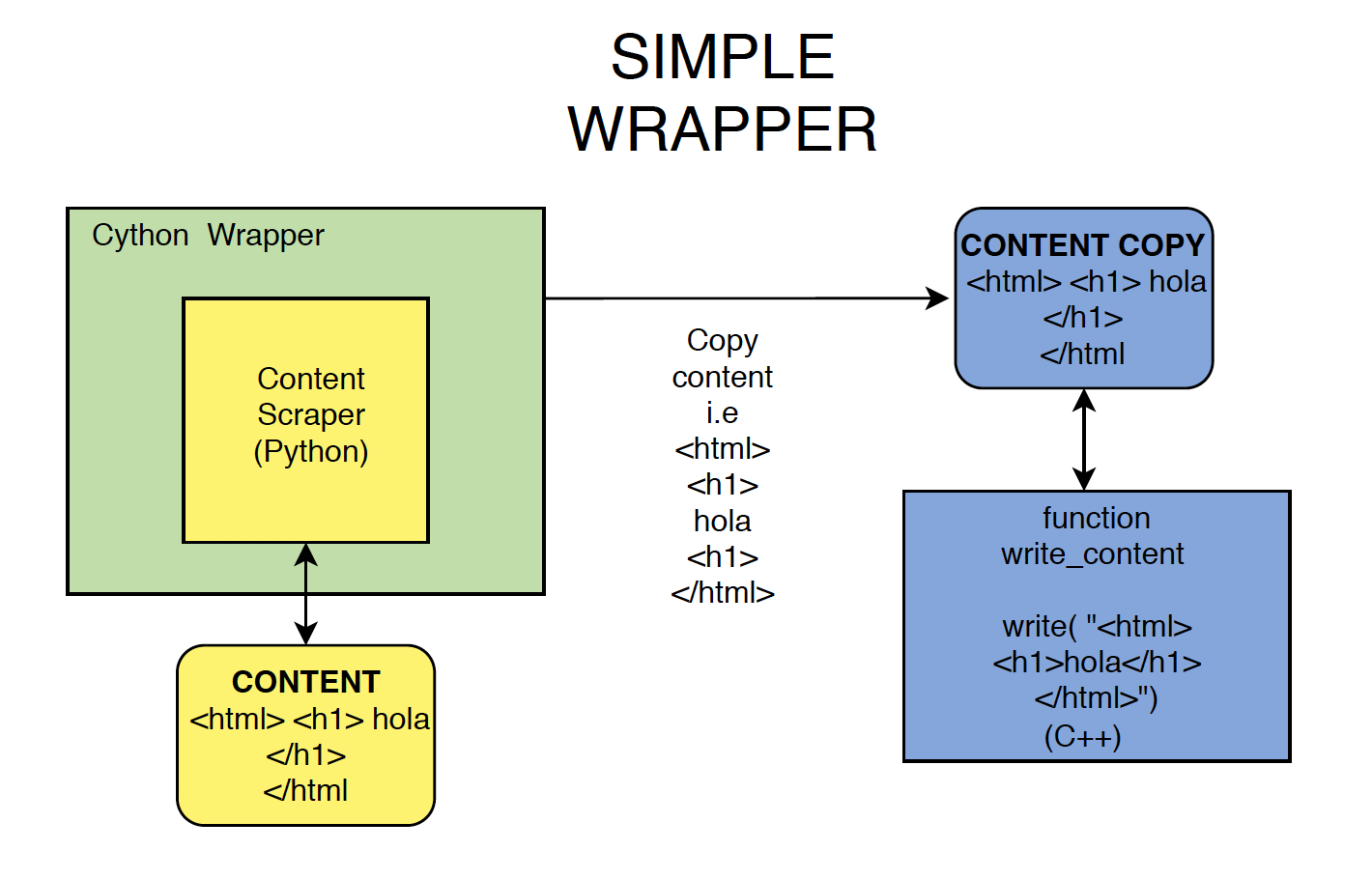

Our job was to create this intermediary mechanism. So we decided to develop a “wrapper” to take Python data structures and translate them to C++. A simple wrapper would pass data (in the form of strings, such as a sequence of characters e.g. “hola”) into the library, from which it could be retrieved with a function:

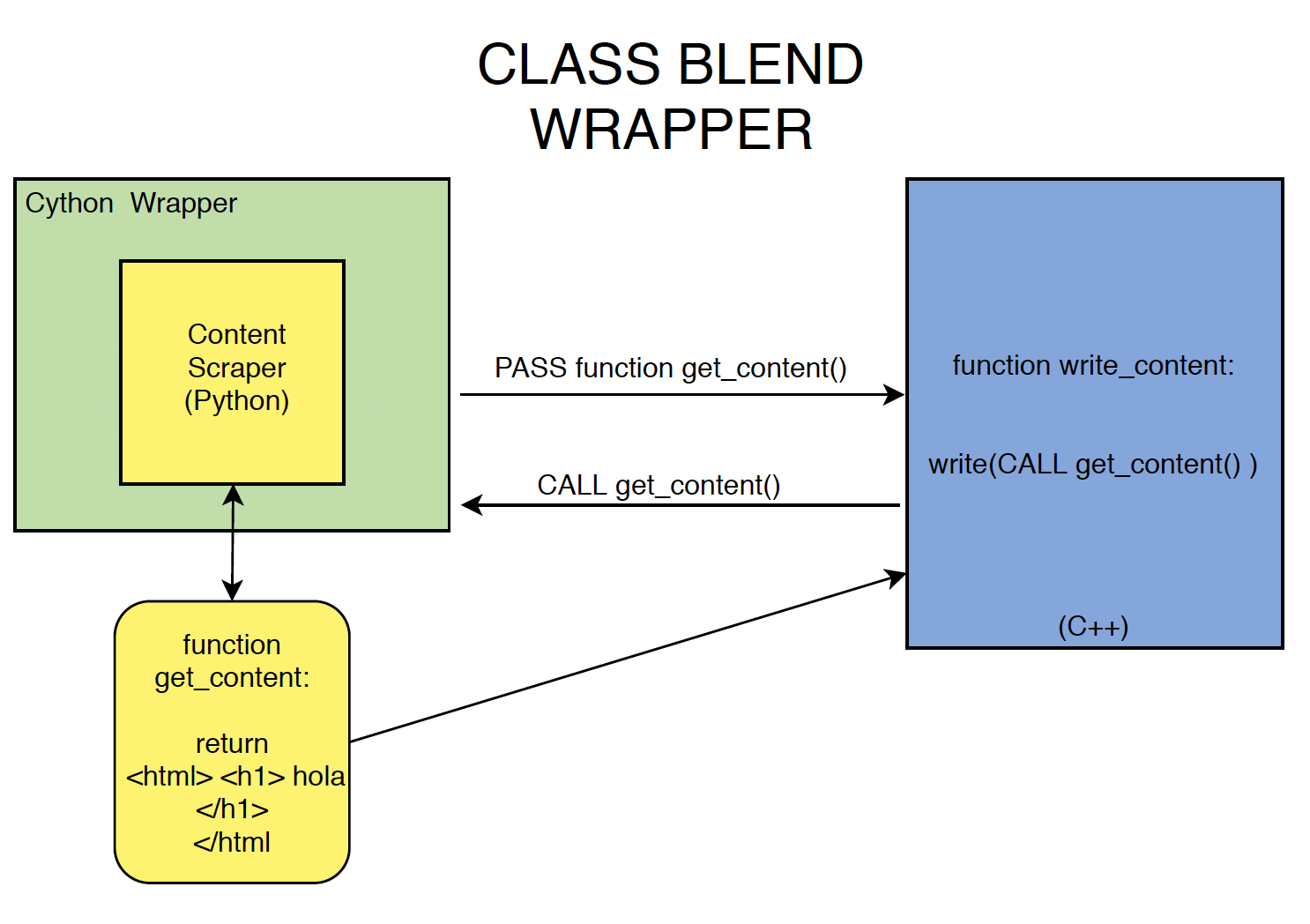

But this posed a problem. The library was expecting input in the form of a function, not a string. Our solution was to create a class blend wrapper, which would allow libzim to get data from Python by passing pointers to Python functions to be called from C++. This was equivalent to implementing a virtual C++ class in python:

Brilliant! A perfect solution, case closed.

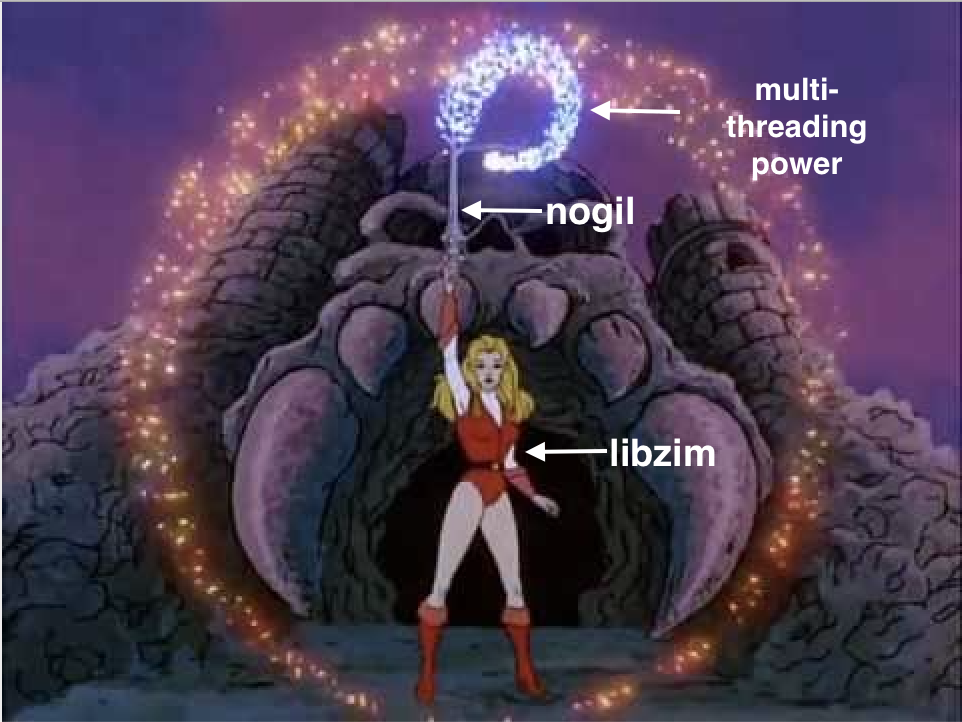

But wait! As the old adage says, a programmer’s work is never done. Once we started to implement this plan, we ran into another issue. Libzim is a multi-threaded library, which means it can execute more than one sequential set or “thread” of instructions at the same time, making it faster and more efficient. However, in Python, while many threads can exist, only one can run Python at a time. This is mediated by a mechanism known as the GIL, or Global Interpreter Lock. So with libzim calling and passing Python functions directly, its multi-threading capacity was incapacitated by GIL.

In order to unleash the multi-threaded potential of libzim, while still maintaining GIL when running Python functions in Python (to avoid memory collisions), we used the ability of the Cython wrapper to run with nogil, so that GIL could be turned on and off. When the library is called, GIL is off, and libzim, much like She-Ra the Princess of Power, has the power (of multi-threading). When data is retrieved from Python by running Python functions, GIL is on, so as not to mess up Python's data and execution.

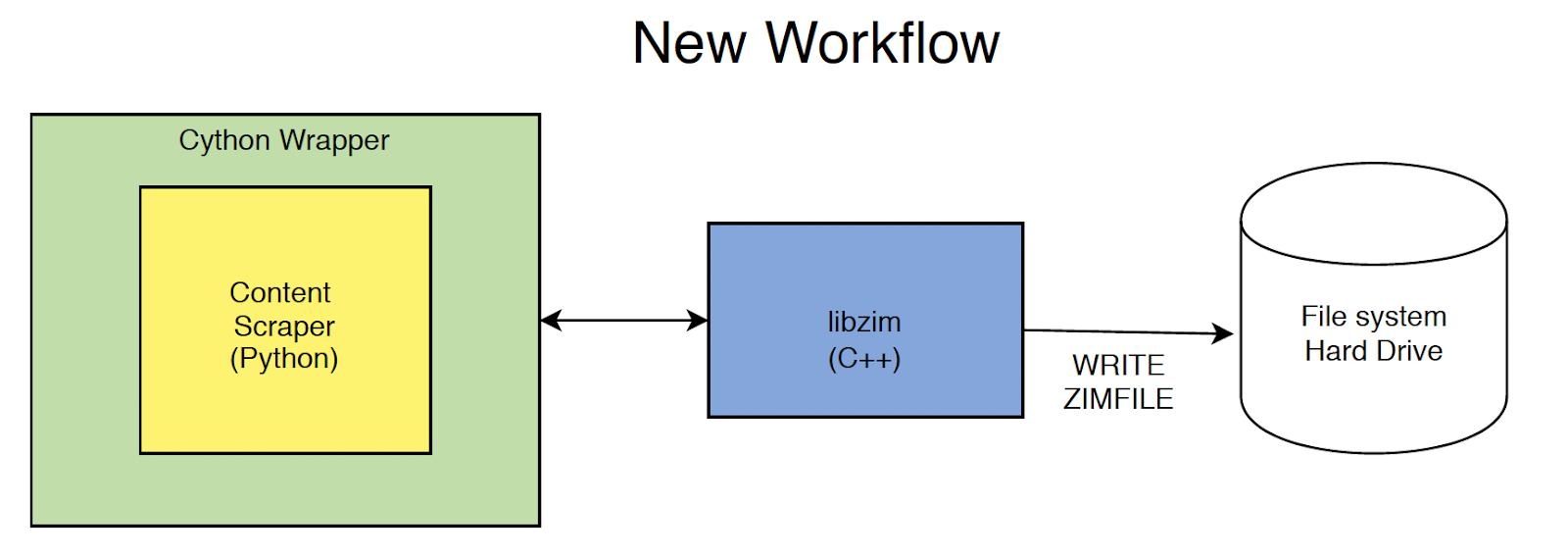

With these adaptations, the old workflow (using Python to scrape the source and copy to a disc (filesystem) and then using another program to bundle content into the library, which could then create the ZIM file) became the new workflow: scraping the source and syphoning the content directly into the library.

The new workflow is faster, easier, and uses Python -- the C++ library is able to call Python functions (not content), and the time- and space-consuming intermediate copy is eliminated. The result is that the library can write more complex sources, since the way that data can be brought in can be manipulated more easily. Overall, the process is more efficient and faster.

We had tons of fun working through the challenges of this project with Kiwix’s team. We hope you had as much fun reading about it as we had doing it! The whole thing is open source, so if you’re interested in taking a look at it, you can find it [here](https://github.com/openzim/python-libzim/).

---

<center>

<img src="https://monadical.com/static/logo-black.png" style="height: 80px"/><br/>

Monadical.com | Full-Stack Consultancy

*We build software that outlasts us*

</center>

---