<center>

# Technical solutions to tackle AI bias

<big>

**Yes, we want more diverse workplaces but there are things on the computing side companies and developers can do to make AIs fairer.**

</big>

*Written by Mirjam Guesgen. Originally published 2022-06-15 on the [Monadical blog](https://monadical.com/blog.html).*

</center>

<br>

In 2020 Twitter users noticed something off when they uploaded images to the platform. If the image was too big for the thumbnail preview, Twitter’s image AI would conveniently crop it to fit. But, the AI was cropping _in_ white faces and cropping _out_ black ones.

>Bad image cropping courtesy of Twitter's algorithm. Image credit: Tony Arcieri.

The company later [apologized](https://blog.twitter.com/engineering/en_us/topics/insights/2021/sharing-learnings-about-our-image-cropping-algorithm) (sort of) and decided that image cropping was something better left to humans than machines.

The Twitter example is not the first, and it’s by no means the last, example of how algorithms tasked with a multitude of jobs – from detecting your face in a picture, to determining who gets healthcare benefits[^first] and who gets arrested[^second] – are biased based on things like gender, race or age.

[^first]:For example, one algorithm used widely in US healthcare settings incorrectly decided a person’s [healthcare](https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.aaz3873) risk because, instead of using the number of chronic illnesses a person had as a predictor, the algorithm was trained using money spent on healthcare.

[^second]:Even more troubling are crime algorithms. There have been several cases where police used [facial recognition](https://www.google.com/url?q=https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/12/technology/facial-recognition-police.html&sa=D&source=docs&ust=1655217459529168&usg=AOvVaw0wR-0-CvF7DyHiVyZdwQNI) to find matches to offenders and misidentifying, and wrongfully accusing, people of colour. [Predictive algorithms](https://www.technologyreview.com/2021/02/05/1017560/predictive-policing-racist-algorithmic-bias-data-crime-predpol/) have sent police to patrol predominantly black neighbourhoods – not necessarily because there are more crimes happening there but because, historically, black people were profiled and arrested more often and that’s what the algorithm picked up on.

Bias in this instance means that the algorithm regularly and repeatedly generates predictions that discriminate against particular groups. This [comes from](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Algorithmic_bias) the system making incorrect associations or assumptions about those groups because of the data it’s been fed, the way it’s been coded or the way it’s been deployed.

Bad algorithms can make life inconvenient for particular groups. Or they can be downright harmful.

Many of the [talks](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tNi_U1Bb1S0&ab_channel=AIPursuit) and articles discussing algorithm fairness have advocates [calling](https://www.ted.com/talks/joy_buolamwini_how_i_m_fighting_bias_in_algorithms) for more diverse workforces (and still calling for it [today](https://theconversation.com/the-tech-industry-talks-about-boosting-diversity-but-research-shows-little-improvement-177011)). Yes, having a wide range of people sitting at the top table, and having better ways of making the voices of minority groups heard, will mean that companies are more likely to preempt biases.

But as well as social efforts, there are also _technical_ steps companies and developers can take to combat algorithm bias.

<div style="max-width:854px"><div style="position:relative;height:0;padding-bottom:56.25%"><iframe src="https://embed.ted.com/talks/lang/en/joy_buolamwini_how_i_m_fighting_bias_in_algorithms" width="854" height="480" style="position:absolute;left:0;top:0;width:100%;height:100%" frameborder="0" scrolling="no" allowfullscreen></iframe></div></div>

## Preparing the dataset

### Better data

Biases can arise from training the algorithms on poor, unrepresentative datasets. Not including particular [ethnic groups](https://dam-prod.media.mit.edu/x/2018/02/05/buolamwini-ms-17_WtMjoGY.pdf) or a diversity of [genders](https://dam-prod.media.mit.edu/x/2018/02/05/buolamwini-ms-17_WtMjoGY.pdf#page=64) or [ages](https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240040793) can mean algorithms have a hard time later when they’re asked to, for example, recognize a face with a particular skin tone or facial feature.

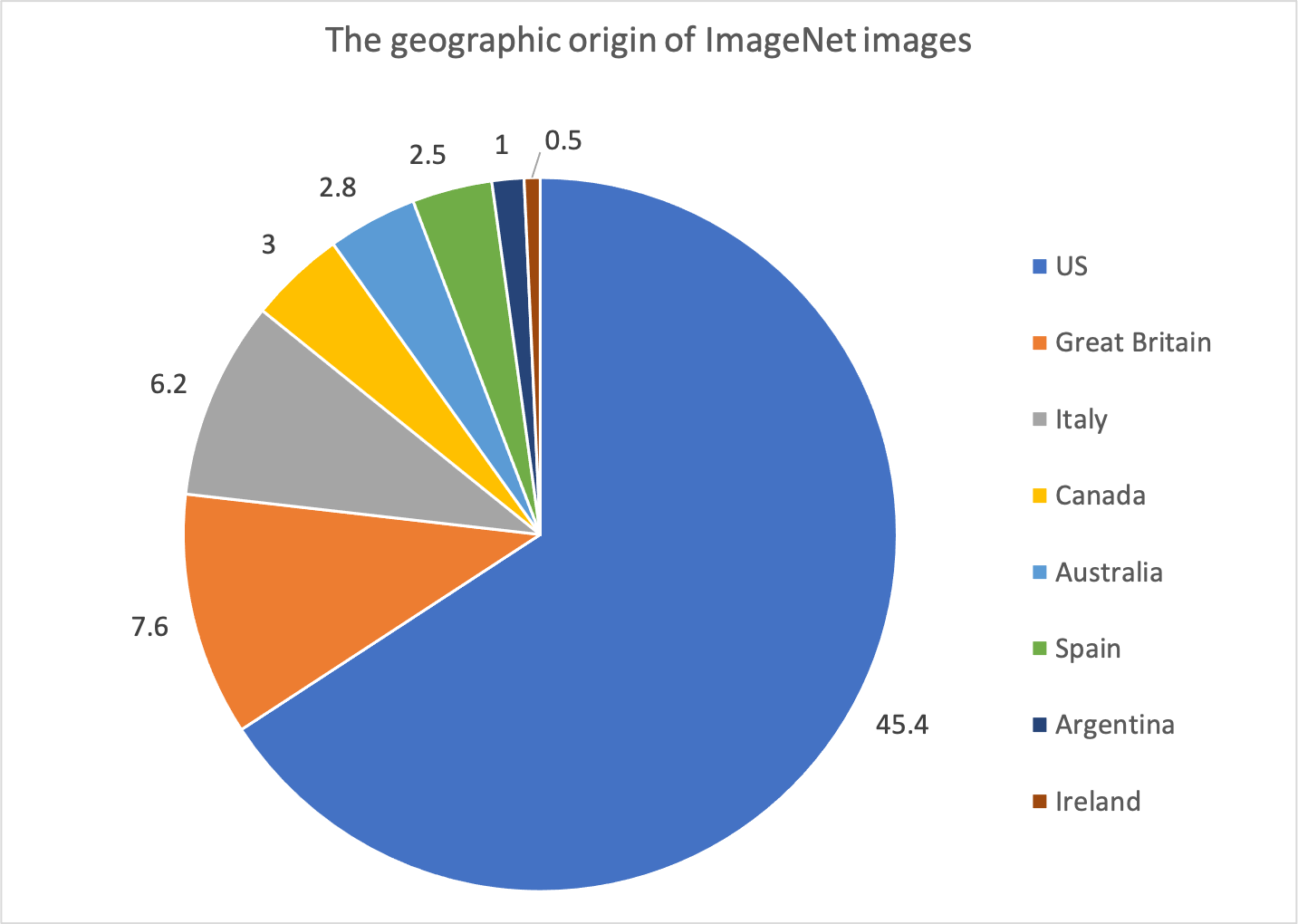

AI equality advocates, like MIT grad and founder of the Algorithmic Justice League [Joy Buolamwini](https://www.poetofcode.com/), have been calling for more inclusive datasets for more than half a decade. In some cases the datasets available were inherently biased, like medical datasets where the sample population itself isn’t diverse enough[^third] or early image datasets that scoured the internet for pictures. The majority of images available to be scooped up for image datasets originated from the [US and Great Britain](https://arxiv.org/pdf/1711.08536.pdf) and so reflected those countries’ and those cultures’ people, interests, landscapes and values.

>The percentage of ImageNet images from each country (note not all countries are shown). The majority come from the US and Great Britain. Original paper [here](https://arxiv.org/pdf/1711.08536.pdf).

[^third]:In one 2022 [review study](https://journals.plos.org/digitalhealth/article?id=10.1371%2Fjournal.pdig.0000022#abstract0), many of the datasets used for healthcare prediction models were from the US (40.8%) and China (13.7%) and almost all of the top 10 databases were from high income countries.

It might seem obvious but the solution in these cases would be to collect data from a wider subset of the population – geographically, ethnically, in terms of gender etc.

But hold your horses, it's not always the case of “more is better”. Just adding more and more data to an already biased dataset won't make it more representative, [experts say](https://dl.acm.org/doi/pdf/10.1145/3442188.3445922#page=5). Some datasets, particularly ones dealing with language or images, have become so massive it’s [nearly impossible](https://dl.acm.org/doi/pdf/10.1145/3442188.3445922) to assess whether they are representative at all[^fourth].

So, instead of crawling the web and creating the biggest dataset possible and assuming diversity, computational linguist Emily Bender and colleagues [suggest](https://dl.acm.org/doi/pdf/10.1145/3442188.3445922#page=5) “thoughtfully curating” datasets that “actively seek to include communities underrepresented on the Internet”.

[^fourth]:§4 in [this paper](https://dl.acm.org/doi/pdf/10.1145/3442188.3445922) goes into why it’s so difficult in more detail. The authors say there’s no one best method for exhaustively discovering all the potential risks with a database. This is because 1. Many of the tools to do so are automated and themselves prone to making the wrong kind of assumptions; 2. Measuring bias means figuring out categories that might be discriminated against. Those categories depend on what cultures you’re talking about and it may not even be possible to list all potential categories; 3. Different groups have different views of what is appropriate and what is discriminatory. I’d add that these points are worth keeping in mind when talking about algorithm hygiene and model testing too.

If it's a thoughtful dataset you're after, why then not just create it yourself? This is known as synthetic data. It's possible to generate synthetic data of [faces](https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/11/21/science/artificial-intelligence-fake-people-faces.html), consumer purchasing or [banking habits](https://mostly.ai/blog/15-synthetic-data-use-cases-in-banking), [geolocation data](https://mostly.ai/case-study/synthetic-geolocation-data-for-home-insurance-pricing/) for fire and flood prediction or [medical records](https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(22)00232-X/fulltext#:~:text=Synthetic%20data%20has%20received%20considerable,relate%20to%20any%20real%20individual).

Creating synthetic data basically [means](https://broutonlab.com/blog/ai-bias-solved-with-synthetic-data-generation#:~:text=Bias%20in%20AI%20doesn't,occur%20due%20to%20biased%20data!) defining and setting the parameters of what a fair dataset would be and then generating data that fulfills that definition. Synthetic data also has a few other nifty advantages, including being able to generate [impossible scenarios](https://openai.com/dall-e-2/) (like a photo of an astronaut riding a horse on the moon) and protecting privacy by not relying on people’s sensitive information – bank records, health records etc – to train the AI.

>An original image made by the [DALL·E 2 AI system](https://openai.com/dall-e-2/). Fake images like this could be used to make fairer algorithms.

One of the more common ways to make synthetic data – and the way many [synthetic](https://hazy.com/) [data](https://www.genrocket.com/) [companies](https://mostly.ai/) do it – is through a generative adversarial network (GAN). Essentially two AIs are first both trained on real data and then pitted against one another to create a dataset that looks most like the real-world stuff. They’re both trying to create a dataset that could trick the other AI into thinking (in inverted commas) that it came from the real training data.

But synthetic data has a big flaw: since it’s AI-made data, it [potentially has](https://hazy.com/blog/2022/01/17/apply-differential-privacy-with-caution/) all the same bias problems as the AIs we’re trying to fix in the first place, if left unchecked. Deb Raji, a technology fellow at the AI Now Institute, has [said](https://slate.com/technology/2020/09/synthetic-data-artificial-intelligence-bias.html) “that process of creating a synthetic data set, depending on what you’re extrapolating from and how you’re doing that, can actually exacerbate the biases. Synthetic data can be useful for assessment and evaluation [of algorithms], but dangerous and ultimately misleading when it comes to training [them].”

There are also questions about how you define what’s fair? Who defines what’s balanced and representative? How do you know a fake dataset is different enough from the real-world one to protect people’s privacy? Synthetic data alone is by no means a perfect solution to algorithm bias.

### Better data labels

Data doesn’t exist in a vacuum. So any talk about better data has to come with a discussion of data labels. That is, how the data within a set are labelled or classified. An example is linking up images with words to describe what the object is and its qualities (the kind of terms someone might search for to bring up a particular image).

>Mislabeling can have very bad consequences indeed. [Source](https://twitter.com/jackyalcine).

Assigning a label to, well, anything is a [subjective](https://dl.acm.org/doi/abs/10.1145/3290605.3300637?casa_token=G8Y3oriasboAAAAA:ZmIRJ_pDaUlHZ4rJswQsQKPG0_HeREyDPewHAU-AZga8CMwxbtS8mN8S7e_Pr4tY9AAtlZ25UA) task. There are literally entire academic disciplines that look at how objects are represented (think art history or semiotics). How do you label an image whose contents are on a spectrum – like how old or young someone is or what their skin tone is? How do you organize the visual world into neat little label boxes?

Historically, image libraries used to train AI algorithms were labeled by a group of underpaid, undervalued, invisible and under-pressure people[^fifth]. The labelers themselves probably had their own assumptions, biases or misconceptions or just a lack of knowledge. Plus, early AI image systems [only allowed](https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/20539517211035955) for one label per image, which obviously became a problem when the image was ambiguous or had several elements in it. This isn’t to say that labelers willfully tagged images poorly. They either didn’t have the skills, the means or there was little to no incentive to do so.

Although labeling will likely always be a subjective or fraught task, there are at least ways to provide better, though never perfect, labels. One is to have more nuanced labels or more categories that you can slot an image into.

[^fifth]:For the full story, check out this really great academic [paper](https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/20539517211035955) from 2021 that traces the history of how the original ImageNet database was created. It shows how financial, labour and time restraints impacted on the quality of the dataset.

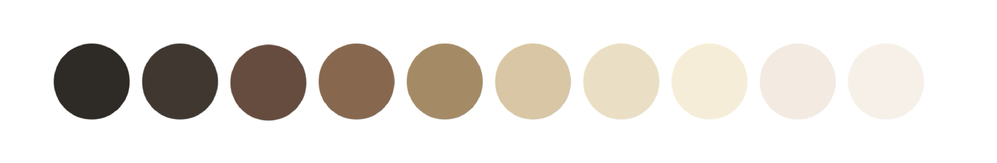

And there have been a few notable examples from Big Tech. For example, Google recently adopted a [broader skin-tone](https://www.wired.com/story/google-monk-skin-tone-scale-computer-vision-bias/) classification range – that now includes a base set of ten skin tones instead of six – to categorise images to [improve](https://blog.google/technology/research/ai-monk-scale-skin-tone-story/) its search, Google face detection when taking photos and [photo editing](https://blog.google/products/pixel/image-equity-real-tone-pixel-6-photos/) tools. It says the tone range can also be used for testing to make sure a range of skin tones is represented in their training datasets or that a camera or image product works for a range of ethnicities.

>The Monk Skin Tone Scale adopted by Google. Reminiscent of attempts at having a wider range of foundation shades.

## Training the algorithm

As well as changing _what_ the algorithm is trained on, it’s also possible to change _how_ it’s trained.

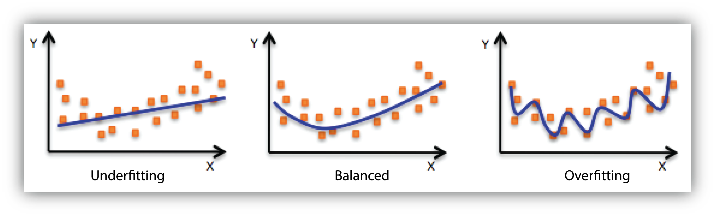

For example, a 2022 [study](https://www.nature.com/articles/s42256-021-00437-5) found that training an algorithm to perform different tasks separately meant the model was better at overcoming bias than if it were trained on both tasks at the same time. A model that's too complex has the tendency to suffer from overfitting, where the model predictions describe the noise in the data rather than the links between variables.

Specifically, this 2022 study looked at image classification. The tasks developers wanted the algorithm to do were grouping images into different categories and recognizing what angle a picture was taken from. Training those two jobs separately meant the algorithm essentially specialized on each task was therefore less likely to make errors.

>Overfitting Summary: Wiggly lines are bad when it comes to model fit.

Yale researchers have also come up with a system called [train then mask](https://ojs.aaai.org/index.php/AAAI/article/view/4251), where the algorithm is given all the information (including features like race, age or gender) during training but then those attributes are masked when it comes time to run the algorithm based on new cases.

It may be tempting to simply tell the algorithm to ignore a factor like race altogether. However, this can lead the algorithm to “cling” to some other proxy variable to explain the outcomes it’s seeing. This is also known as latent discrimination. Partly, latent discrimination crops up because the algorithms are designed to optimize for the best result – the most accurate predictions based on the information given.

Take for example an algorithm designed to predict the likelihood of reoffending[^sixth]. It might predict that a certain race is more likely to reoffend, but that’s based on those people being profiled and arrested more often, even if they’re innocent. Even if race is removed as a variable of the model, if those people tend to live in the same area, the algorithm may instead link reoffending to location.

The model needs the original variable (race, age, sex, whatever) to make sense of the patterns in the data its fed and not give extra importance to proxy factors. But, you as a developer or algorithm user don’t want the algorithm later making decisions based on that variable. You want people to be treated the same at this step. In the reoffending example above, the masked algorithm would essentially treat every person as white.

“Train then mask emphasizes helping disadvantaged groups while enforcing that those who are identical with respect to all other – non-sensitive – features be treated the same,” [said](https://insights.som.yale.edu/insights/can-bias-be-eliminated-from-algorithms) the method’s co-developer Soheil Ghili.

Algorithms developed using train then mask have performed almost as well as algorithms trained using the standard method, with what the researchers say is only a “very small loss in accuracy” For example a model that was trained without constraints correctly predicted whether an individual’s credit score risk is low or high 75% as well as the original data compared to 74% using train then mask. This while significantly reducing discrimination and latent discrimination[^eighth].

[^sixth]:This is obviously a huge issue socially as well as technologically. More on that [here](https://www.propublica.org/article/how-we-analyzed-the-compas-recidivism-algorithm) and [here](https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.aao5580).

[^eighth]:The definitions and measurements of these are super technical but you can find them on page 3677 of the [paper](https://ojs.aaai.org/index.php/AAAI/article/view/4251).

## General good AI practice

Ok, but how can we put all these ideas together into something do-able? You’re a developer sitting at your desk staring at your monitor, or maybe you’re the new boss charged with implementing a new AI. What do you do?

One way to combat bias is for companies and developers to do some “algorithmic hygiene” whenever they’re creating or editing code.

>Monadical does not endorse this^ kind of algorithmic hygiene.

At the outset of development, this [means](https://ai.google/responsibilities/responsible-ai-practices/?category=fairness) considering who the algorithm is for, whose views are represented and what’s being left out of the dataset. Ideally, it means creating goals about who the algorithm is for and what its intended use is, then monitoring this through development and deployment.

When it comes time to test the algorithm, getting a diverse pool of testers, who can put the algorithm through a series of adversarial tests, can hopefully mean preempting any biases. There are also several tools available – including IBM’s [Watson Studio](https://www.ibm.com/cloud/watson-studio/model-risk-management) or Google’s [What-If](https://pair-code.github.io/what-if-tool/index.html#about) – for testing whether an algorithm is fair in terms of features like gender or age[^fourth]. Watson Studio, for example, lets people request a challenge model, made by IBM’s developers and data scientists, to compare their algorithm to. What-If works as an extension in coding platforms like Colaboratory or Cloud AI Platform. It’s a visual tool to show developers how fair their algorithm is based on [definitions](https://pair-code.github.io/what-if-tool/ai-fairness.html) like everyone getting an equal chance statistically.

Finally, algorithmic hygiene means monitoring and adjusting the algorithm once it’s deployed in the real world. This means paying close attention and actually acting when users call attention to a [flaw](https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2020/sep/21/twitter-apologises-for-racist-image-cropping-algorithm).

Most of the Big Tech companies, including [Google](https://ai.google/responsibilities/responsible-ai-practices/?category=fairness), [Meta](https://ai.facebook.com/blog/how-were-using-fairness-flow-to-help-build-ai-that-works-better-for-everyone/) and [Twitter](https://blog.twitter.com/en_us/topics/company/2021/introducing-responsible-machine-learning-initiative), have posted summaries in the past year of steps they take that resemble algorithmic hygiene. They at least are trying to be more transparent, if only within the company, about their algorithms. For example Meta has introduced comments, also known as model cards, alongside machine learning models that detail how the model works, its intended use, where the data is coming from and evaluation reports[^seventh]. However [some](https://blog.twitter.com/en_us/topics/company/2021/introducing-responsible-machine-learning-initiative) of these responsible AI guides focus more on fixing mistakes of the past than ways to ethically develop new algorithms.

[^seventh]:[Here’s](https://modelcards.withgoogle.com/face-detection) an example for Google’s Face Detection algorithm.

## More than lip service

And perhaps monitoring and actually responding to instances where things go wrong is one of the most important steps to combat algorithm biases. After all, we – users, companies, developers – don’t know what we don’t know. There are still plenty of [examples](https://www.wired.com/story/opioid-drug-addiction-algorithm-chronic-pain/) of issues with algorithms only being identified after the tech has been in use for some time.

It might also be that, sometimes, decision making is better [left](https://www.vox.com/future-perfect/2019/4/19/18412674/ai-bias-facial-recognition-black-gay-transgender) to a person than a computer, like for criminal cases or police surveillance. At very least, having a human looking over an AI’s shoulder.

No person or tech is infallible, but at least developers, [ethicists](https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2022/01/irs-should-stop-using-facial-recognition/621386/), [advocates](https://www.wired.com/story/social-inequality-will-not-be-solved-by-an-app/) and [academics](https://www.theatlantic.com/family/archive/2020/10/algorithmic-bias-especially-dangerous-teens/616793/) can keep breathing down tech’s neck to get things right.